Life book text

LIFE UNDER DEMOCRACY

At a pavement café, behind dark, ever-present Ray-Bans, Yudelman sits watching a woman walk down the sun-beaten road. With each step the city’s pavements gnaw at her soles – vigorously testing the mettle of the voluptuously proportioned Winnie-the-Pooh slippers adorning her feet.

Rising mid-Americano, inwardly delighting at the colourfully shod parade heading his way, he fumbles an apology and takes off after the flamboyant pair. Nobody minds the curt exit. Waiters instinctively know he’ll be back; friends accept that being in his vicinity places them on a permanent photo shoot.

Yudelman swings into his approaching-without-malice gait – best described as an unaffected stroll. A casual air is a necessary posture for a tall man about to converge on the path of a stranger.

For a while, he says nothing, keeping a safe, friendly following distance. The entire odyssey – from noticing to the point of making contact – has set off a mixture of purposeful calculation and a heady desire to enthrone the pyjama-shoes in all their chunky, why-are-you-on-this-pavement glory.

Inconsistent conditions and never-to-be repeated moments are what make this uncertain playground an infinitely compelling storybook of unfolding possibilities.

After several decades of wielding an array of film and later digital cameras, considerations such as light, background and best angles are calibrations that go on automatically in his brain.

The question of relevance hovers nearby, like a reliable but overbearing parent. Undeterred, Yudelman stays close to the fascination. Instinct tells him the bright yellow pavement specials have an interesting tale to tell.

But first, there is the matter of clearing some personal barriers: his innate shyness and a culturally ingrained precept of respecting the privacy of others. This is possibly the least comfortable moment of street photography – striking up a conversation with an unknown entity.

By now, he has shadowed the woman far enough to gauge something of her state of mind. She notices his genuine interest. Somehow they begin to talk. And there on the tarmac, in the sunshine, a story unfolds.

In the first few seconds, it’s about the warm weather, an easy unifier, they both experience this day as equals: it is on this even plane that Yudelman prefers to keep this kind of interaction. Sensing her openness, he compliments the celebrity slippers and asks if he can take a picture with his phone.

Caught up in the playful web of his request, stopping for a snapshot seems reasonably normal. After taking a few pics, he shows her how they look, she’s happy they only reveal the smiley bears – and not the face belonging to the scarred legs that have just left the day clinic, about to carry her to a night shelter a couple of blocks away.

Quarrying for answers in the murky regions of the blindingly familiar is what Dale Yudelman does best. In his testament of the lives of fellow South Africans, in a country deep in the throes of a pubescent democracy, people, events and even objects become part of contemplative essays interpreting how front page news permeates into the fabric of the collective experience.

Life under Democracy was inspired by the Ernest Cole exhibition at the National Gallery in Cape Town, in February 2011. Cole’s images feature life under apartheid. Yudelman’s series looks at life under democracy after eighteen years of liberation.

Many of the images were shot in passing and are personal daily reflections, while others involve more deliberate excursions. In Life under Democracy, Yudelman returns to the areas he photographed in the eighties, for the series Suburbs in Paradise, which cross-examines white suburbia under the influence of legislated segregation.

To gain perspective, he also visits some of the people and areas Cole photographed. A sense of how much has changed begins to develop and, in some cases, how much has stayed the same.

In a country where old anger is amplified by new barriers imposed in the course of its almost two decades of democratic rule, where infringements of power and corruption bear the same watermark as the injustices of apartheid, the question he asks is: How would Mr Cole feel about the freedom he dedicated his life to achieving?

As if in conversation, Yudelman uses his iPhone camera as a means of discourse. The senses are unified through a device historically utilised for discussion, in turn mirroring the merging of a nation whose past is omnipresent.

His images easily bear the burden of portraying issues and feelings as distinctly as if they were actual objects. Transforming the social experience into knowable, tangible material where the viewer gains access to the emotion of the moment, enables further research along tributaries feeding the cause or circumstance.

Yudelman’s observations are benefited by a photographic career beginning in the late seventies, starting out as a photojournalist for The Star newspaper at the height of the political turmoil in South Africa.

For the past fifteen years his focus has been on his personal work, with exhibitions shown in galleries around the world. His artistic bent for decoding social landscapes is fully realised in the art space – producing work infused with a quirky visual vernacular.

Life under Democracy reveals a nation learning to live beyond the confines and within the liberties of two opposing systems: the first, extinct but not silenced; the second, crafted with the highest hopes of freedom in mind. The story is of our response and participation in realising the full extent of those dreams as viewed through the eyes of a well-versed protagonist.

His experiences of past and present set the co-ordinates for this self-imposed brief. Yudelman scours the foreground of the public domain, where he taps into the backstory, looking for less tangible indicators of change.

The opening image presents the first democratic ballot paper issued in 1994. Eighteen years later this early relic of freedom is considered old enough to be sold along with other memorabilia in an antique store, its price tag serving as a reminder of the time when the idea of a democratic South Africa was, for the oppressed, a prized imperative; for others, a dangerous idea: and for all, a highly charged proposition in the silhouette of a prejudiced unknown.

A sprawling cultural diversity as profound and disparate as South Africa’s is no more obvious than at heritage sites. While the history is based on the same facts, the similarities begin to disappear when examining the emotional content of memories and the impact they have on the psyches of different ethnic groups.

The series gives an insight into the challenges of remembering the past and understanding the scale of what is implied in finding meaningful validation for all. Among such jagged recollections: one man’s hero is another man’s villain – where even God is not innocent.

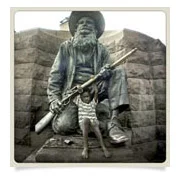

At the other end of the rainbow, Yudelman highlights a child playfully hanging from the rifle of an unknown Boer soldier, a statue at the Paul Kruger Monument in Church Square, Tshwane. The child almost blends into the sculpture, becoming a living addendum to the bronzed past (p21).

Straddling the impressions of our adolescent democracy, Yudelman gives a lucid account of the socio-political topography with all its awkward insecurities, frustrations and rebelliousness. Within these reflections, we see the concerns of a fledgling nation afraid to be seen to be becoming like its betrayers; and how these replications in some instances already go beyond a prediction.

The assertion of a new national identity, complicated by a disfiguring and dysfunctional past, is currently pock-marked by greed, corruption, high levels of unemployment and dropping standards in healthcare, education and general living.

As much as he points out and celebrates individuals within the multitudes, confident in their full and unrestrained national voice, applying for equality, in search of equilibrium and a sense of worth, so he also refers to the angst of a country – in and out of step with an evolving understanding of itself: the practice and the concept of democratic freedom.

Studying the emergent horizon, the work gives a transactional analysis of the scale of cultural exchange required, and the subcutaneous issues of racial division. It reviews the chasms created by the racial segregationist policies of the apartheid government, which led to South Africans becoming economically and culturally dualistic and disassociated.

The signs and symbols pictured in the series reference inter-cultural engagements and present responses in surprising places: a woman wearing Orlando Pirates earrings – a sport and team better known in this country for its predominantly black male supporters (p181).

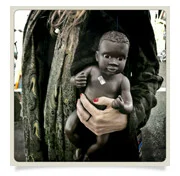

Another image that uses this style of referencing is ‘woman and doll’ (p91). Here the image provides a gateway to the complicated levels of social integration, which, while essentially portraying a positive shift, is also laced with ambivalence around white people adopting black babies. The price on the doll flaunts the idea that it is easier to adopt a black child, as there are many more black children up for adoption due to poverty and the problem of an ever-escalating number of AIDS orphans. Although this practice is quite accepted, there are still the concerns around children losing their cultural heritage through cross-cultural adoptions

Life under Democracy unravels a succession of stories within a story; a multi-layered transcription articulated with an effortless visual fluency. Yudelman is not merely quoting from reality, but, like any good storyteller, allowing his subjects to describe themselves. Revelling in the spontaneous spirit of South Africans, the work mirrors a nation full of promise and an extraordinary ability to be expansive.

In spite of the difficulties they experience, and sometimes because of the on-going challenges, their lives are a compelling demonstration of strength and unfettered resilience in the face of boundless uncertainty. Values become apparent through the portrayal of the spaces in which they work and pray, what they eat and where they shop. The essay draws attention to profound instances of devotion in caring for fellow citizens; impossible miracles requiring enormous strength of character; and a capacity for nerve-straining enterprise.

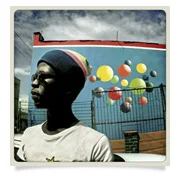

Yudelman began experimenting with the concept of using his iPhone for documentary images shortly before the inaugural Ernest Cole Award was announced. On winning the award, he made a point – as part of the Life under Democracy series – to visit Mamelodi Township where Cole grew up (p217).

During his meeting with the Kole* family members – some of whom still live in the same house – he was introduced to Moses Mogale, now a well-known jazz musician and music teacher in the community (p193).

The iPhone camera finds its destiny providentially and immutably altered in Yudelman’s masterful hands. Throughout the series he utilises the square-format hipstamatic app which simulates the effects of the old-fashioned disposable film and Polaroid cameras. Designed to produce the unpredictable results of the early darkroom, it randomly saturates the image with colour, or washes it out. With a selection of built-in digitised retro lenses, films and flashes, it conjures up some of the alchemy of the once highly chemical process of developing.

The intensified field created by the formatting matches Life under Democracy investment in interpreting the fine print of daily life. Unhindered by oversized equipment, he achieves a visual rapport that is exquisite and robust all at once. His portraits are vibrant, poetic studies of the constant stream of conversation between people and their environment – intimate disclosures of the interior realm of his subjects spilling into view.

Using spatially compelling compositions, Yudelman maintains a tight grip on the material world by limiting the amount of information in the image.

Intrigued by the ironies of life he invites the viewer to share his amusement at the contradictions that surround us. ‘Protests’ (p28) shows the second day of heavily-supported protest action in Cape Town. Demonstrators in full cry are about to go on a blind rampage. In the scene, to the left of the crowd and from his position in the middle of the drama, he still manages to throw in a headline from the previous day, which reads, ‘Municipal strike gets off to a SLOW start.’ It is at these junctures that Yudelman ambushes what might have been a straight photojournalistic shot and successfully expands the image to include a mischievous comment on mass media and its defining role within reality.

Commanding subtleties form powerful optical snares in league with Yudelman’s ethics of eschewing brash imagery (unless absolutely required), allowing what he chooses to leave out of the frame to speak as distinctly as what he chooses to include.

From the floor of a flea market in Cape Town, he invokes a chilling omen commenting on the fate of the rhino – a wooden statuette of the pre-historic creature with the horn missing (p74). Impossible conversations, spanning alternate dimensions, are a defining feature in this series: the viewer is easily guided to the place where what is salient is not overshadowed by sensationalism.

Photographing on the street means that a considerable amount of his time is spent sifting through the clenched reality of everydayness, always in search of yet another clarifying dimension. His images reveal the rich chronicles that flow beneath the surface of the flurried ordinary. It is within the backdrop of these surprisingly regular mirrors that we see ourselves with heightened clarity.

* Cole, born Kole, managed to have himself reclassified as ‘coloured’ in order to evade the Pass Laws restricting the movement of black people.

words - © Simone Tredoux 2012